Infamous Mothers: Expanding the Face of Heroism

Introduction

In my self-care kit, I have an array of items: manicures, pedicures, long showers, hot baths, extended walks, and more. However, when I'm feeling burnt out and need to unplug from life, my favorite go-tos are Netflix, Hulu, Prime Video, and the like. I indulge in binge-watching movies that transport me to faraway lands filled with dragons, witches, warlocks, and heroes. Lately, though, I've found myself craving something different, something more personal. I've been yearning for fantasy movies where I can see myself, my life, and people like me as the heroes and magical beings. I no longer have the mental fortitude to bridge the gap between the faces and stories I see on screen and my own life. As I face my own dragons and overcome the supervillains in my life, I long for the inspiration that comes with seeing a fantasy or sci-fi version of me doing the same.

Being the hero of your own story, the one who saves yourself, can be immensely challenging, especially when you lack a clear vision of what that entails. It becomes even more daunting when you've been painted as the problem or as someone incapable of making a difference, or even when you're portrayed as so powerful that you're no longer seen as a human being. This blog post aims to expand the conventional notion of who can be a game-changer, a trailblazer, and someone who makes a difference. It introduces new faces and storylines to the hero's narrative, welcoming the women we call Infamous Mothers into the spotlight. This is about broadening the scope of heroism to include those who are balancing motherhood with the pursuit of their wildest dreams—a true hero's journey. Sadly, for badass moms who are out there doing extraordinary things, this quest is often underexplored and underimagined in popular culture and literature. And when it is represented, it doesn't always portray a complex and full woman. It's time to rewrite this narrative, to represent the multifaceted aspects of these ambitious moms and inspire them as they chase their impossible dreams. Let's redefine heroism and motherhood and create a world where the stories of these ambitious moms take center stage, not linger at the fringes or, worse, remain ignored and untold.

Reimagining Heroines

In a world where heroines and heroes have traditionally been defined and celebrated from a predominantly white, male perspective, it's time to explore a fresh set of ideas and images that resonate uniquely with the women of the Infamous Mothers world, or the IMverse. The concept of Infamous Mothers as heroines aims to provide a perspective that represents not only our women and communities but also goes beyond the clichéd portrayals dominating popular culture and literature.

But First, A History Lesson

Traditional heroes and heroines are often defined by their noble qualities, closely associated with the ideals of white men. In Black culture, one version of that kind of heroism can be behaviors associated with respectability politics. Between 1900 and 1920, women from the Baptist church promoted a movement that mixed good manners and morals with traditional forms of protest, boycotts, and vocal demands for justice. But the problem with this approach is that it was rooted in assimilationist practices, which, while meant to counter racist stereotypes, ultimately reinforced white racist practices. Respectability politics aimed to combat beliefs that portrayed black women as inferior. For instance, they meant to combat stereotypes that the "bad black mother" was at the heart of black families' decline, or that black female teachers were responsible for the failure of black schools.

Nella Larsen, author of “Quicksand”.

However, the Harlem Renaissance (early 1900s through about 1940) challenged respectability politics, showing that upholding white practices in the name of countering racism undermined their mission. Writers and blues singers, in particular, began to illustrate how instead of saving the black race, women who promoted respectability politics were ultimately supporting their own oppression. Nella Larsen, for instance, wrote "Quicksand," in which the main character, Helga, ends up marrying a pastor and having multiple children for him while he enjoyed support from the women in his congregation, and she was confined to her bed, tired, feeling degraded and hopeless. She pushed out child after child for a man who reaped the benefits of being a leader while leaving her to live alone in the corner of his life.

Then came the blues women. Singers like Bessie Smith and Ida Cox shattered respectability. Their music was provocative, sexual, and filled with references to same-sex relationships. They were seldom portrayed as mothers or wives in their songs. Their focus wasn't solely on their children, even when they were mothers. Their identities extended beyond their roles in the home. They wanted to be seen as independent women with concerns that went beyond one aspect of their lives.

Bessie Smith, blues singer

As we moved into the Black Arts Movement, motherhood was represented in various ways, from a woman struggling to abort a pregnancy to a mom 'losing her mind' to a mom being a ‘queen’ or ‘goddess’ symbol. However, through all of these, there were very few representations of black women who were both not respectable— single moms or teen moms, or women who had multiple children by multiple men— and who were portrayed as change-makers in society. Even up until the 1980s and to the present day, there have been very few representations of heroic motherhood that exist outside the boundaries of respectability politics. As a society, we seldom imagine the "bad girls" of motherhood as heroes or individuals capable of making a change in our world.

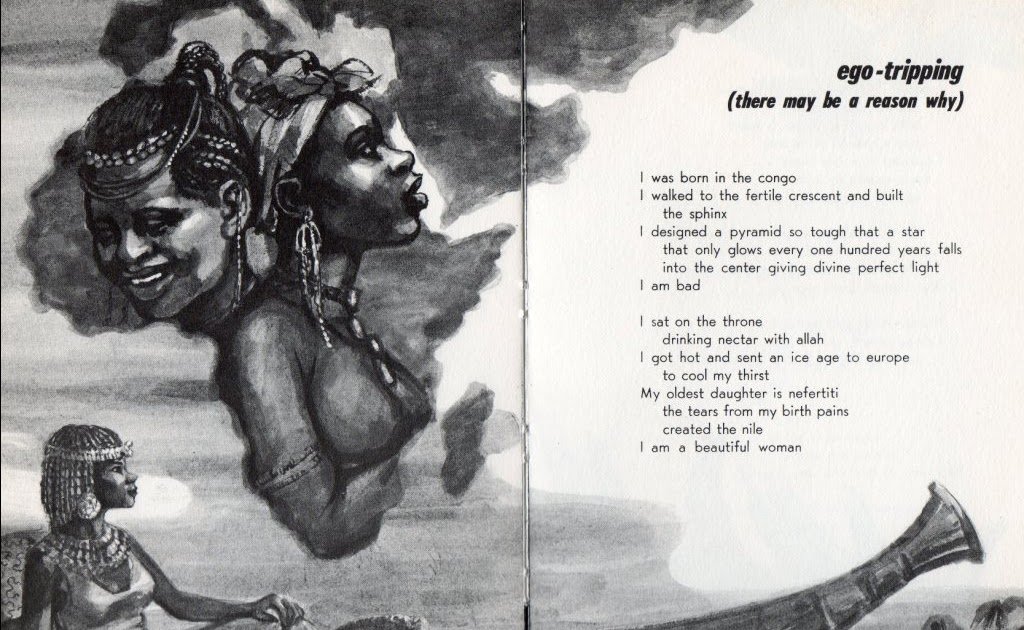

An excerpt from Nikki Giovanni’s poem, “Ego-Tripping (there may be a reason why)”

The reason behind this is the rhetoric surrounding motherhood. According to Professor Lindal Buchanan, "mother" is a "god term" associated with self-sacrifice, martyrdom, protection, and the home. Moms can be heroes, but often only for their children and within the confines of their homes. They are often not seen as capable of making a difference in the public sphere. They can't save communities or nations or worlds. On the other hand, "woman" is a "devil term" associated with sensuality, self-centeredness, and the public. There's tension between what it means to be a mother and a woman in society. In America, in particular, we have quietly agreed that these two categories (mom and woman) must remain distinct. The blues woman (and her descendant, the hip-hop woman) choose freedom over being respectable. This meant they chose to be vilified and possibly judged for not being "good" mothers. Up until recently, with Cardi B and her daughter Kulture, virtually no hip-hop woman was represented as a mother. Think of Lauryn Hill, who created a whole album dedicated to her first-born son, Zion, and then disappeared from the world of music and the public eye.

It's almost as if we made a pact with white patriarchy, one that resembles the one Adam and Eve made with God. "You are free to eat from any tree in the garden; but you must not eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat from it you will surely die." Similarly, black women seemed to have been told by the white men in power, "You are free to challenge any oppression around womanhood, but you are not meant to confuse women with mothers, or you will surely be judged and vilified. You can't be sexual and a mother. You can't be a hero in public and a good mother in private. Ambition and motherhood don't mix." For these reasons, it was very rare to see a black woman represented on television or the big screen as a warrior and a mother. And even now, I challenge you to name five superheroes who are black, mothers of small children, and individuals who save the world or the nation. But this is just a piece of the representation problem.

Championing Unconventional Heroines

If such a hero existed as a single black mother, a teen mom, or a recovering addict mom who saves the day, we would call any of these women "antiheroes." In other words, she would be a hero who deviates from our traditional heroic archetype. The issue with this is that, like respectability politics, it would still be rooted in a white perspective. For many people, this woman would simply be a hero, as she is the standard for them, an ideal. This is yet another reason to expand and offer a different model of heroism, one that reflects the experiences and viewpoints of Black women and women in general as the norm. We need to rework the framework of what it means to be a hero to be more inclusive and representative of all kinds of people who need to see themselves and be inspired. We have to do this not just for the women themselves but for the world to see.

Balancing Vulnerability and Power

There's a fine line to walk when reimagining black women as superheroes. On one hand, we come from a history that has depicted us as able to endure high levels of pain. The medical establishment, for instance, has a long history of ignoring black women's pain due to the biased belief that, because of our race, we have a higher tolerance for suffering. Being portrayed as superhuman has dehumanized us, causing others to dismiss the pain and hardships we endure in crises and in everyday situations. This is one reason why black women die in childbirth at three times the rate of white women.

Halle Berry as Storm in X-Men.

On the other hand, when we imagine game changers, heroes, and the future of the world, black women, especially mothers, are often left out of those pictures. To be clear, they do exist. Think Storm from X-Men, the movies, or Thunder and Lightning, the two sisters from Black Lightning. There are also powerful women who are heroes, even though they do not have superpowers. Think Okoye and Shuri from Black Panther or Michonne from The Walking Dead. But these women are not the norm in a world full of white saviors. We're usually missing from representations of the future in any capacity. And when we are present, we are not usually portrayed as people who are making a difference or an impact in society—that's typically reserved for white men. In the rare cases that we are present, it is because a black woman writer made it possible.

There are more representations of white women in this superhero capacity. They range from Wonder Woman to Supergirl to Black Canary and the Wasp. Even with this wider range, very few women with superpowers, regardless of race, are mothers. While a handful of superheroes and supervillains are mothers in the comics—Storm, Tygra, Catwoman, Batwoman, Ms. Marvel, etc.—that position is mainly reserved for Elastigirl from The Incredibles on the big and small screens. Black Panther presents us with a powerful queen, and we learn that Nakia shares a child with King T'Challa. However, for years, only Elastigirl has been represented as someone who is in the fray, fighting the bad guys and saving the day—and living to tell about it. Recently, we've been blessed with a big-screen newcomer, Jessica Drew (Spider-Woman), who is pregnant, black, and a superhero. Also, we have Nanisca of the Woman King who is a warrior and a mother, but of a child that she didn’t raise. Aside from these rare representations, it's often portrayed as a trade-off between having powers or surviving. Those seem to be the two options reserved for mothers who want to make a difference in the world.

Elastigirl from “The Incredibles”

Because representation matters, I wanted to offer an image of black motherhood that is relevant now and in the future. I wanted her to be powerful but also vulnerable. I wanted her to be someone we can imagine as kicking ass, saving lives, having a love interest, and being cared for, while also caring for others. What does that look like? I wanted these women to be based on or inspired by real women whom we've seen and admired so that we can see ourselves in them and embrace our powers without apology. My goal wasn't to create black, female versions of white heroes, but to create our own, based on what matters to us in our culture, specifically what matters to the women we call Infamous Mothers. And so, I categorized them in the form of eight archetypes for us to choose from.

Here they are:

1. Healer

She has the power to treat wounds and injuries, making people whole again. Her capacity extends beyond the physical. She is able to cure emotional and physical wounds, too.

2. Speller

This woman is charismatic and can captivate you with her words. She can mesmerize you as she delivers a pitch. She can soothe you with her voice. With the right combination of words, she can transform lives and outcomes.

3. Storyteller

Her magic lies in her ability to write and rewrite stories, creating herself and others through her narratives. While she is a sister to the speller, the storyteller's magic is more specific.

4. Shapeshifter

This woman can transform herself from one physical form to another. From changing her style to changing her hustle to changing her entire body, she can become whatever the occasion calls for to fulfill the mission.

5. Disarmer

Her ability to tell the truth, "keep it 100," or "a buck" is second to none because the way she does it inspires and motivates women to drop their masks and live more authentic and genuine lives.

6. Wielder

Her influence and use of power are unparalleled. She can harness, control, and lean into her sexuality, embracing the chaos of orgasms, as opposed to running from them. Throngs of people follow her across social media, blogs, and podcasts. Effortlessly, she is able to affect the lives of others, their behaviors, and her own.

7. Protector

Whether it is dreams, people, spaces, or emotions, this woman's superpower is not only keeping them safe but doing so until the end.

8. Subversive

She disrupts ideas, spaces, behaviors, etc., that seek to oppress and undermine her family, community, and nation.

In literature and popular culture, heroes typically fall under these categories: Epic, classical, everyman hero, tragic hero, Byronic hero, reluctant hero. But for our purposes— for the women I coach, the women who attend our retreats, the women who read our blogs, build with us on social media and read our newsletter— those categories don’t serve us because they don’t speak to our journey of juggling ambitious goals with mothering.

Conclusion: Celebrating Ambitious Moms as Unconventional Heroines

In our journey to redefine heroism and motherhood, we have embarked on a quest to shine a spotlight on the extraordinary and ambitious moms who have, for too long, been relegated to the fringes of popular culture. As we close the pages of this narrative, we leave behind a resounding call to action, urging all of us to expand our perception of what it means to be a hero and to recognize the superheroes among us.

The Infamous Mothers: Women Who’ve Gone through the Belly of Hell and Brought Something Good Back

We have witnessed the struggles and triumphs of Infamous Mothers, a term we've coined to celebrate these women who tirelessly navigate the intricate balance between motherhood and the pursuit of their wildest dreams. Through their incredible stories, we have been introduced to a diverse array of heroines who represent the vibrant tapestry of our society.

From the Healer, who mends both physical and emotional wounds, to the Speller, whose words captivate and transform lives, to the Shapeshifter, who adapts and thrives in diverse circumstances, and to the Protector, whose unwavering commitment keeps dreams and emotions safe, these women break the mold of conventional heroism.

But it's not just about celebrating these unique archetypes; it's about transcending stereotypes and biases, whether rooted in respectability politics or societal expectations. It's about recognizing that every woman can be her own kind of hero. Our definition of heroism should be as diverse as the women who strive to make a difference.

In this journey, we've encountered challenges, such as the fine line between portraying black women as powerful and vulnerable, and the unfortunate scarcity of representations of mothers who are also change-makers in the world. However, as the blog suggests, we have the power to rewrite this narrative, to challenge these stereotypes, and to create our own heroes, inspired by our unique culture and experiences.

Representation matters, not just for the women themselves but for the world at large. By telling these stories and offering a range of heroines, we hope to inspire others to recognize their own superpowers, to embrace their ambitions, and to break free from the constraints of traditional expectations.

So as we conclude, remember this: Heroism knows no boundaries. Motherhood, ambition, vulnerability, and strength are not mutually exclusive. In this beautifully complex and ever-evolving world, every woman has the potential to be a hero in her own story. We encourage you to celebrate the hero within, and to continue rewriting the narrative, one empowered and ambitious mom at a time.

Also, to join the conversation about this blog post on social media, follow Infamous Mothers on Instagram: infamous.mothers.

Discussion Questions:

1. How has the blog changed your perspective on heroism and motherhood? What key takeaways resonated with you the most?

2. Do you believe that societal stereotypes have impacted your perception of ambitious moms? How can we challenge and change these stereotypes?

3. Can you think of examples in popular culture or media where ambitious moms have been portrayed as unconventional heroines? How did these representations impact your views?

4. How do you balance your identity as a mother with your ambitions and dreams? What strategies do you use to navigate this complex terrain?

5. What are your unique superpowers, as an ambitious mom or as a woman in general? How can you harness these powers to make a difference in your life and in the world?

6. In what ways can we collectively work to expand the representation of ambitious moms as heroes in our culture and media?

7. Consider the eight categories of heroines mentioned in the blog (Healer, Speller, Storyteller, Shapeshifter, Disarmer, Wielder, Protector, Subversive). Which archetype do you resonate with the most, and why? How might this archetype apply to your own life?

8. How can we foster a culture that supports and empowers ambitious moms as they pursue their dreams and redefine heroism?

ABOUT THE BLOGGER

Dr. Sagashus Levingston is an author, entrepreneur and PhD holder. She has two fur babies, Maya and Gracie, six children (three boys and three girls), and they all (including her partner) live in Madison, WI. She loves all things business, is committed to reminding moms of their power, and is dedicated to playing her part in closing the wealth gap for people of color and women. She believes that mothering is a practice, like yoga, and she fights daily to manage her chocolate intake. The struggle is real, y’all…and sometimes it’s beautiful.

Follow her on Instagram: @infamous.mothers